World of Glass 2026 Report

Float supply may return to Canada and high-performance technologies seek greater market purchase

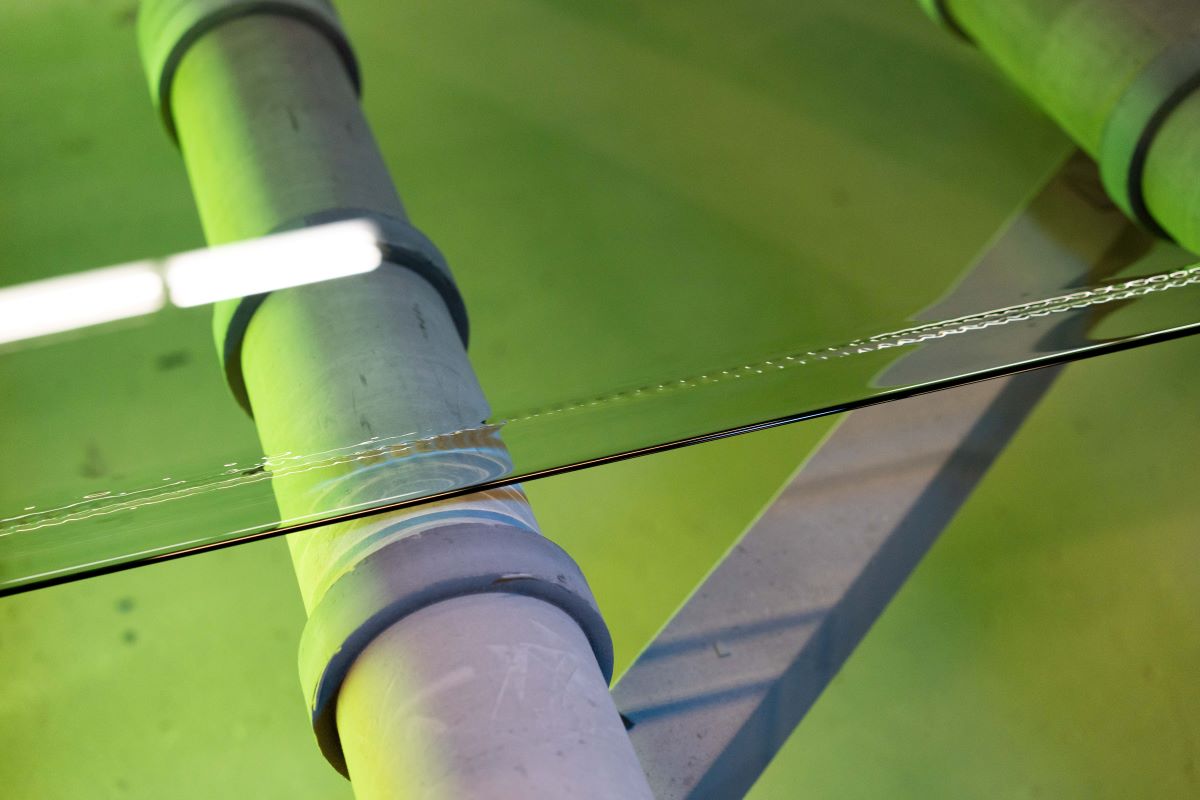

Above: Glass is processed through the tin bath at the Hautcharage, Luxembourg, manufacturing facility of Guardian Glass.

The World of Glass used to be simpler, and smaller. I know from my time reading through back issues of Glass Magazine that architectural glass started life as a more standardized product, expanding in applications, competition and supply in the post-war era. And since the National Glass Association was founded in 1948, float and raw glass manufacturing has only continued to innovate across the world and across architectural applications to become a high-performance material.

Today’s glass industry is anything but simple. The last year has seen significant economic turbulence caused by tariffs as well as rising inflation and costs. Despite this, glass industry companies have worked to secure, and even expand, float glass supply, while also continually innovating more energy-efficient and sustainable solutions in the form of vacuum insulating systems, solar patterned glass and now thin glass solutions.

Updated World of Glass Map

The National Glass Association hosts the World of Glass Map, a comprehensive industry resource working to represent the glass building products supply chain. The World of Glass offers two ways to interact:

- Find an interactive map at glass.org/world-glass-map. Map users can find information about global float glass manufacturing locations, top-grossing North American glass fabricators and their fabrication capabilities, as well as U.S. recycling facilities. Locations can be browsed or searched for by name and location. The online map is continually updated with new information. If you don’t see a location you feel should be included, let us know!

- Download the World of Glass Map database. Newly updated as of August 2025, this sortable spreadsheet features three separate databases representing different parts of the supply chain: a global float manufacturing database, a North American glass fabricator database, and a U.S. glass recycling database.

Float, fabricator and recycling databases all include company name and location information. Additionally, the float database includes the number of float lines (as is available) and the fabricator database features reported fabrication capabilities.

Resources from the National Glass Association

Download the following resources from glass.org/store:

Tariffs reshape float and patterned glass supply in unexpected ways

Fernando Diez, vice president of marketing, Vitro Architectural Glass, says that the “new reality” resulting from tariffs have “impacted the supply chain at all levels, including our customers.” Nevertheless, the company has been working to increase domestic production capacity and local sourcing, he says. “Fortunately for Vitro, this has not impacted us given the flexibility of our manufacturing network, where we are able to leverage our capacity of shifting production across our North American assets to accommodate demand. We also anticipated these challenges and have been transparent with our network of customers to ensure minimal impact to operations.”

Alan Kinder, director of demand creation at Guardian Glass, says that the fluctuating tariffs have impacted fabricators and the glass industry more broadly. “Fabricators that have historically imported glass have changed to domestic sourcing or are sourcing from countries with lower glass tariffs,” he says. The new tariff environment is also pushing more onshoring of solar panel production and automotive glass, he says, which is consuming a large portion of North American glass supply. Unlike the increase in demand after COVID, Guardian Glass reps say a slow recovery over several years is more likely to see a return of market demand.

Glenn Leroux, president and CEO of Canadian Premium Sand, says the new tariff environment has had a negative effect on new investment and new ventures on the part of the company. Canadian Premium Sand announced in 2021 that it was planning to bring float glass manufacturing back to Canada after the country’s last float plant closed in 2008. Then, given the incentives the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act offered for the production of solar panels, the company revised their plan to instead produce solar patterned glass, Leroux explains. Canadian Premium Sand’s low-iron sand deposit is ideal for creating the ultra-clear glass that solar panels need, he says, and patterned glass manufacturing is “an easier business,” requiring a fairly standard product with the same coating for about five to six customers.

As of 2024, the company had been planning to open patterned glass facilities in Selkirk, Manitoba, in Canada near the company’s sand deposit, and was simultaneously reviewing two potential sites in the southern U.S., both former container glass factories, in order to establish an American location. But once the new tariff environment took hold in 2025, financing the project became much more difficult. “A number of the policies that were creating momentum for the U.S. manufacturing base, they still created momentum, but the incentives related to that momentum were under threat and remain under threat,” says Leroux.

Leroux describes what followed as a “perfect storm,” as offtake agreements with potential customers, needed to ensure financing for the facility, became harder to come by as costs to complete the renovation fluctuated. To make matters worse, the cost of solar patterned glass fell below $6 per meter, which also disrupted potential financing. Leroux says the reason for the drop in costs is a combination of factors, including cheap freight prices for solar glass imports—which for North America tend to come from China, Thailand and Malaysia—as well as the greater global capacity of solar panel manufacturing and increased competition worldwide.

“We certainly haven't given up on the U.S. [solar patterned glass] project, and we absolutely have not given up on the Canadian project. But those are the headwinds that we’re facing, and they’re not trivial,” Leroux says. He also emphasizes that though financing has been difficult, and incentives for investing in the industry may be shifting, demand for solar panels is here to stay, largely driven by the need for cheaper power in the U.S. “We all believe that if we had a facility right now, and we were producing solar patterned glass, even in Canada, we’d sell out.”

Canadian Premium Sand is not the only North American glass industry player interested or involved in solar panel manufacturing. At the beginning of 2025, NSG Group converted one of its float lines at its Rossford, Ohio, factory to produce transparent conductive oxide glass to supply solar panel manufacturer First Solar. First Solar also announced a $330-million investment in a new North Carolina facility as of November 2025.

In 2024, Vitro Architectural Glass began investigating the possibility of adding patterned solar glass capacity to its facility in Wichita Falls, Texas. Vitro’s Diez emphasizes that the Wichita Falls investment is still in process, and would not affect the company’s architectural glass production, but says that domestic production of glass for solar panels has wide industry interest. “We know that current partners and potential clients are excited about supporting the production of American-made patterned solar glass. Domestic sourcing of this key solar module component simplifies supply chains and ensures reliable product delivery,” he says.

In what could seem like an ironic twist, the changing economic environment has led Canadian Premium Sand to reconsider their original proposition: building a new float plant in Canada. Leroux says the company is officially “investigating the viability” of opening a float facility, the first Canadian float plant to be built in decades.

Vacuum insulating glass and thin glass sectors expand

While solar panel production continues to grow, other innovative glass technologies are beginning to accelerate, including vacuum insulating glazing and thin glass for multi-cavity insulating glass units. Both high-performance technologies are poised for greater market adoption.

Regional codes and energy costs could push greater VIG adoption

As of 2025, all three of the major North American float companies supplying the commercial market have VIG options available, including NSG Group Pilkington’s Spacia, Vitro’s exclusive agreement to supply VacuMax in North America, and Guardian Glass’s development partnership with Denmark-based Velux. This last year also saw some new players in North America, including Kolbe Windows & Doors’ partnership with LuxWall to incorporate VIG into Kolbe’s window and door products.

VIG provides similar or superior thermal performance to conventional double glazing, in the thickness of a single glass lite, according to the National Glass Association resource “Vacuum Insulating Glazing, an Introduction.” The gas in the space between two lites of glass is extracted to create a vacuum, rather than filled with air or argon as a traditional IGU would be. The glass lites remain separated by pillars (also called microspacers) approximately 0.005 to 0.012 inch (0.15 to 0.30 millimeter) thick. The thin profile of a VIG can be installed in new construction, in restoration projects, including as a secondary glazing; and refrigeration applications.

Despite VIG’s strong performance, Vitro’s Paul Bush, vice president, sustainability, technical services and government affairs, says that VIG will remain “niche” until current energy codes and stretch codes catch up to the product’s insulating qualities. “Updating these codes and standards is crucial to fully leverage the potential of VIG and promote more energy-efficient buildings,” he says. “Without the driver of code requirements, the adaptation will likely be slow and gradual, and it could take up to a decade to see any notable increase based on current codes.”

Codes may not be the only potential driver of VIG adoption. Chris Fronsoe, national architectural manager for the Northwest region at Vitro, says that strained energy resources might result in more adoption of the high-performing solution. He points to the significant rise of data center building, used to support infrastructure for artificial intelligence. “Cities will likely have to share their energy grid with these installations, and that could mean that energy will be at a premium,” he says. Data supports Fronsoe’s claim—AGC of America’s Data Digest reported statistics from ConstructConnect that year-to-date data center spending has increased 92.8%, amounting to $32.9 billion in investment. Fronsoe says that such a strain on energy resources could push further adoption of an energy-efficient solution like VIG.

Guardian Glass’s Kinder says the company sees the most demand for VIG in commercial retrofits of historic buildings and in luxury residential. He describes VIG as “an exceedingly small market that is at the beginning of its new product growth curve, about to take off,” and says that many colleagues feel that it will be the glazing solution for northern climates in North America.

While VIG offers superior insulation performance, it also reduces embodied carbon compared to traditional systems, an indicator that industry leaders say is still on the radar of the design community and regional governments. Guardian’s Kinder says that architects, developers and regulators continue to demand “reliable, transparent data on the environmental performance of materials—and Environmental Product Declarations have become an important way to provide that information.” Vitro’s Paul Bush says that while there may be a perception that federal interest in the embodied carbon of building products is on “pause,” state and regional legislative trends “indicate a continued focus” on this area of sustainability, as does customer interest. “This regulatory momentum at the state and region level underscores the imperative for a reduced carbon future,” he says.

Barriers for greater VIG scalability remain the capital costs required to install a VIG fabrication line, says Guardian Glass’s Kinder. “It’s significantly more expensive to install a VIG line compared to traditional IG production. Not every window manufacturer who currently creates IGs can create VIG.”

Industry collaboration leads to innovation in thin glass systems

Another high-performance glazing option is multi-pane windows that use thin glass as the center lite(s). Currently, the companies that manufacture architectural thin glass include Cardinal Glass Industries, NSG Group, Asahi Glass Europe, Guardian Glass and Corning Inc. While no standard industry definition yet exists, thin glass is considered to be less than 0.098 inches (2.5 mm) thick.

While thin glass and its use in glazing systems is not new, recent industry collaboration has resulted in an increase in production capacity for the specialty glazing. Partnership among Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, or LBNL0—as well as industry players like Corning, Alpen High Performance Products, Miter Brands and machinery manufacturers like Glaston, Erdman and Hegla—are allowing for greater potential use of the material in glazing applications. Other machinery manufacturers like Forel also offer machinery for fabricating thin-triple IGUs.

LBNL was instrumental in innovating the first thin-triple pane window in the 1980s. Conventional triple-pane windows have existed since early in the decade, offering more insulation than double-pane IGUs. However, the addition of an extra glass lite means by definition more weight, larger width and higher cost. Berkely Lab researchers developed a thin-triple-pane window in response to these difficulties, creating a glazing solution to cut energy costs while also creating a lighter, narrower system. LBNL researchers say the technology was put on hold until there was a way to manufacture large sheets of thin glass.

That technology arrived in the late 2000s spurred by new thin glass applications in smartphones and other media technologies, creating demand and reducing manufacturing costs. NSG Group developed their 0.3mm Ultra Fine Flat, or UFF, glass for electronic applications in the early 1980s, according to the company’s website, and built a float line for mass production of the glass in 1988. In 2014, NSG released its glanova thin glass, a clear, chemically strengthened composition glass manufactured through the float process. They began to expand applications of the glass, including architectural applications, the next year.

Not all thin glass has to be produced using a float glass method, where raw materials are melted on a bath of hot tin to form flat glass. The thin glass manufacturing process developed by Corning scientists Dr. Stuart Dockerty and Clint Shay in the 1960s instead used gravity, according to the company’s website. During this process, molten glass is flowed into an open trough, shaped in a V. The force of gravity then pulls the glass down on either side, with streams meeting at the point of the V, which are eventually drawn into a sheet.

Chelsea Tracy, director of architecture at Corning, says that compared to traditional soda lime float glass, “thin glass has better performance in terms of breakage, less embodied carbon, more uniform appearance and is more optically clear due to having 50% less iron content.”

Safety glazing certification remains a hurdle to broader market adoption

Despite its performance and sustainability benefits as part of a multi-pane IGU, one hurdle to thin glass architectural adoption in the U.S. remains its ability to be certified as safety glazing, a topic discussed by industry and technical leaders at NGA Glass Conference: Ann Arbor in 2025. To be certified, the thin glass IGU would need to be certified by the Safety Glazing Certification Council to have passed testing by ANSI Z97.1, which provides a test methodology and specification guidance on how to test glass or "permanently" bonded safety materials like laminated, filmed, mirrored and VIG (2025 version). The building code requires that all lites in a glazing system must be tempered or laminated glass. The challenge for these systems is that thin glass cannot be tempered, and to laminate it would eliminate the other benefits of a thin glass IGU. Currently, the thinnest glass certified monolithically is 0.098 inches (2.5 mm), according to Kristin Best, program manager for SGCC.

Stephen Morse, associate teaching professor and head of the Architectural and Structural Glass Research and Testing Lab at Michigan Tech, shared strength testing results of different thin glass systems at NGA Glass Conference: Ann Arbor, which suggested that broken pieces of thin glass would not result in laceration when broken, though data collection is ongoing. Robert Hart, principal scientific engineering associate at LBNL, questioned the industry as to whether ANSI Z 97.1 is even the correct standard to evaluate thin glass. “Tempering was designed as a proxy for safety. You’re not testing if the glass is safe or not, you’re testing if it breaks into a small size,” he says. “Thin glass breaks differently—do we need a different test?” Discussions will continue at ANSI, SGCC and NGA as more test data becomes available.